Paradox (In)Security Systems: IP150 Internet Module Hijacking

Paradox Security Systems is a Canadian company manufacturing alarm systems and various security devices since 1989. One of their most popular family of products are the IP150 internet modules. They are used with their SP, MG and EVO series security alarm panels to enable control and monitoring of the security alarms over the Internet. In this article we will show how insecure these widely used devices are and how we could completely disable the security of tens of thousands security systems all over the world.

If your home, company, or office is protected with one of these security alarm panels in combination with an IP150 module, then it can be fully compromised by relatively simple means, as one of the vulnerabilities we found allows anyone remotely, without any proper authentication to overwrite its firmware with a custom firmware image not only to disarm the physical security, but potentially gain a foothold inside your network.

Vulnerable devices

Our testing was done on the IP150 and IP150+ devices with their latest firmware (5.02.019/5.03.000).

The IP modules run on a STM32F4 MCU with an ARM Cortex M4 CPU, have an ethernet port and connect to the alarm panel and receive power through a serial connection. They come in three models IP150, IP150S and IP150+, these product versions differ only in minor ways and all provide the same major functionality, the ability to monitor and control your security alarm over the network.

Scope of the problem

These devices are popular all over the world. To get some estimation about their popularity we can use an OSINT service such as shodan.io. As the IP modules have a web interface (or at least had, as Paradox seems to be transitioning away from it, but more on that later) with a unique favicon.ico icon, the favicon hash search from shodan can be used to see how many devices it knows about. The following query gives an overview on how widely they are used:

https://www.shodan.io/search?query=http.favicon.hash:-1205024243

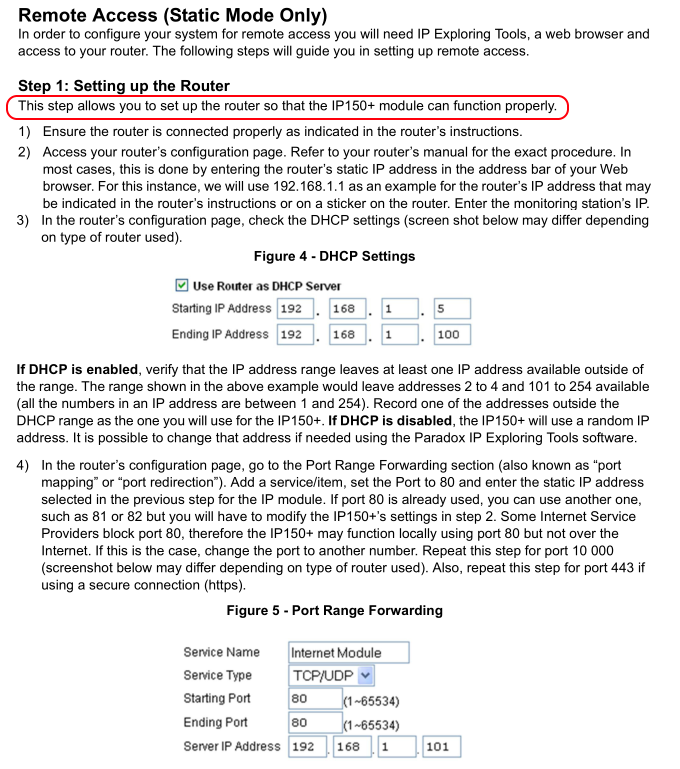

Shodan finds 33,000 devices all over the world, of course not every device is indexed, so the total number is probably significantly higher, especially if we consider that some of them are not exposed to the internet but likely still can be accessed through the SWAN protocol (Paradox solution for managing devices through the cloud). It also helps us that one of the first things Paradox tells you to do in their installation manual is to enable port forwarding on the router for the Web UI and communication ports and expose them to the internet.

Operation of the device

As mentioned before these devices are relatively simple, their main purpose is to act as a serial-to-ethernet proxy for the security alarm panel. This is done over a proprietary Paradox protocol, by default using the TCP port 10000. To manage the security alarm, you can find a few choices of software, the main one being their Insite Gold mobile application available for Android and iOS. There’s also the BabyWare application available only for Windows and some open source projects such as PAI (Paradox Alarm Interface), all of them are able to connect to these devices using the proprietary protocol.

The IP modules also have a Web UI which over the years had functionality removed from, not that it had a lot to begin with as it was never meant to manage the alarm system, only the IP module itself, and with the most recent 5.03.000 firmware update for the IP150+ module the web UI was disabled completely.

It seems that Paradox wants its customers to solely use their Insite Gold app, where features such as their cloud connectivity service SWAN costs money, and only technicians licensed by distributors of Paradox products can change certain installation settings.

SWAN is Paradox’s implementation of STUN which helps with communication with devices behind a NAT. In this article we will only be using direct connections, but majority of our found issues should also be exploitable over SWAN.

The proprietary protocol

This protocol Paradox products use does not have any public documentation, analyzing it will leave you an impression of legacy code where not much has changed for a long time. Our testing was made faster by reverse engineering work done by contributors of the PAI project. It was very helpful as they have implemented a subset of the whole protocol to develop a working client. Additionally, a wireshark protocol dissector also exists, though it is based on the work by PAI project and does not fully decode most of the messages.

The protocol itself is composed of binary “IP messages” which are made of a header and a payload which is usually encrypted with AES-256 ECB. There is no server identification, meaning that messages can be easily intercepted and tampered with if an attacker is able to execute man-in-the-middle attacks. There is also no MAC or any other kind data integrity protection besides simple CRC checks, so it is possible to inject data into the encrypted messages.

IP messages have several types and commands. The following IP message types exist:

- IP request – IP messages meant for the IP module itself.

- IP response – responses to IP messages.

- Serial passthrough request – encapsulated serial messages that the IP module passes to the alarm panel, while the protocol for these is similar to IP messages, it is slightly different and differs between EVO/MG/SP panel product families.

- Serial passthrough response – encapsulated serial response messages from the alarm panel.

In this article we will mainly work with IP messages meant only for the IP module, these have the following commands, as defined inside the Insite Gold mobile application:

- cmdSinglePanel

- cmdBootIP

- cmdBootLoader

- cmdConnect

- cmdDisconnect

- cmdKeepAliveRequest

- cmdMulticmd

- cmdPassThru

- cmdReset

- cmdSendUserLabel

- cmdSetBaudRate

- cmdToggleKeepAlive

- cmdUNDisconnect

- cmdUnsuppRequest

- cmdUploadDownloadDisconnection

- cmdUpploadDownloadConnection

- cmdWebPageConnect

- cmdWebPageDisconnect

The commands can be executed after authenticating with the IP module password, which is hardcoded and cannot be changed. Then there are serial commands, which go through to the alarm panel, using a different format. These require full authentication using the IP password and the usually guessable PC password, or similarly weak user codes.

Authentication

There are multiple layers of protection/authentication in place with these security alarm systems. The first one is the “IP password”, this password is used in every user session when communicating with these devices over the network. Authentication with this password must be done before you can execute the IP commands. Starting from 4.x firmware versions this IP password is set to “paradox” and cannot be changed at all.

The second one is what Paradox calls the “PC password”, it is the password that is used when connecting to the security system with an application such as BabyWare or the firmware upgrade application InField, knowing this password will allow you to take complete control of the security alarm system. This password is a 4-digit hexadecimal code and by default is set to 0000, to change it you must navigate to an obscure part of the BabyWare application and Paradox does not require for it to be changed during installation. Older manuals of the IP module used to recommend that this password should be changed, but newer versions of the manual have removed this recommendation for some reason. There is brute-force protection, which gives you 20 tries before the system is locked up for 3 hours or is reset by power cycling the device. Given that this is only a 4-digit hexadecimal number, it is not that hard to guess this password in a couple of lockouts, and majority of alarm systems probably have not changed it at all.

Finally, there are the user codes, these are 4- or 6-digit decimal numbers that users punch in the actual alarm keypad to arm or disarm the alarm. They are split into regular user and master codes. The master codes can also be used to login to the IP module’s web UI or login and manage the actual alarm through the Insite Gold mobile application.

To go a bit deeper into technical details we’ll describe how a fully authenticated session is established, the following steps usually happen when a client such as BabyWare connects to the security alarm system:

- An IP message command cmdConnect is sent with the hardcoded password “paradox” as a payload, encrypted with AES-256 ECB, with the key also being “paradox”.

- The IP module responds with an IP message which contains an 8 byte hexadecimal encoded session key, the serial number of the IP module, firmware and hardware versions.

- An IP message command cmdUpploadDownloadConnection is sent which is needed before serial messages to the alarm panel can be sent.

- A serial command InitiateCommunication is sent encapsulated and encrypted using AES-256 in ECB mode with the received session key, inside of an IP message of serial passthrough type, the response of the module contains information about the alarm panel, such as its serial number, firmware version and other information.

- A serial command StartCommunication is sent in the same manner, with the response containing some additional information such as the alarm panel ID.

- Finally, the InitializeCommunication serial command, once again encapsulated and encrypted inside an IP message is sent, it contains the PC password, and if it’s correct the session is established and the alarm system can be fully controlled.

Now as we are somewhat familiar with the protocol in use, we can investigate the actual vulnerabilities in the IP modules.

Reset DoS vulnerability

This is the simplest issue we discovered, you might have noticed that one of the IP commands is cmdReset, which does exactly that – resets, or rather reboots the device. To cause a denial of service you can just authenticate with the cmdConnect command, of course using the hardcoded password “paradox” and send the cmdReset command. After receiving the command an IP module waits for about 8 seconds and then reboots. You can keep doing this indefinitely to interrupt any monitoring process and prevent a proper security response from happening.

Dangling session vulnerability

As described in the authentication section to fully authenticate you need both the IP password and the PC password, this can be bypassed due to a dangling session vulnerability. When a user fully authenticates and disconnects by, for example, closing the Insite Gold or BabyWare applications an internal serial session remains active for 1 minute. If this internal serial session for communication between the IP module and the alarm panel is still active an attacker can connect to the IP module, authenticate with the hardcoded IP password, issue the command cmdUpploadDownloadConnection, and afterwards start sending arbitrary serial messages. In a normal scenario this would result in an error, all the serial messages such as ReadMemory would return an authentication error, but during the 1 minute window an attacker can take over this dangling session and take complete control of the alarm system.

The following video illustrates this issue, where a script connects to the IP module every five seconds, authenticates with the IP password, sends a cmdUpploadDownloadConnection command and then attempts to read the PC password and user codes from the memory of the device. As can be seen at first it fails, but when an authenticated user closes the BabyWare application the internal session can be reused and the codes are read without full authentication.

An attacker could just keep running this attack indefinitely until an actual user connects and then disconnects from the IP module.

Firmware update vulnerability

This vulnerability allows anyone who has access to an IP module over the internet to overwrite its firmware with a custom image. A firmware image could be created in a way that it would act as a persistent backdoor to the network it is connected to.

Before 4.x versions firmware of IP modules used to be updatable through the InField application, which is part of the BabyWare software package, by uploading the firmware file through the application to the module. Later firmware versions saw the implementation of “remote upgrades”, where the process has changed and the upgraded firmware is downloaded from the Paradox upgrade server, a user just selects the version in the InField application.

The firmware update process starts with an application such as InField authenticating using the hardcoded IP password, and sending an IP command cmdBootLoader with a payload such as this:

0000 a5 4c 00 30 71 07 a1 0d a9 6c a4 9f b9 00 00 57 .L.0q....l.....W

0010 02 16 70 72 6f 64 2f 69 70 31 35 30 5f 64 65 66 ..prod/ip150_def

0020 61 75 6c 74 2e 70 75 66 22 75 70 67 72 61 64 65 ault.puf"upgrade

0030 2e 69 6e 73 69 67 68 74 67 6f 6c 64 61 74 70 6d .insightgoldatpm

0040 68 2e 63 6f 6d 3a 31 30 30 30 30 61 h.com:10000a

This packet includes the product type, the module’s serial number and more importantly, it has a file name of the firmware and a hostname of the upgrade server. The IP module that receives this packet connects to the specified host from where it downloads the firmware. Of course, communication with the upgrade server happens through another proprietary protocol, which is unencrypted, has no authentication or any means of identifying that the server is a legitimate upgrade server.

The upgrade protocol is simple, the connecting IP module exchanges a couple of packets with the upgrade server containing some information such as serial numbers, product versions and etc. Afterwards the file transfer starts, and the upgrade server sends out an obfuscated firmware image in 1024 byte chunks. It finishes with the upgrade server sending out a packet with a 32 byte CRC. This CRC must match the CRC of the transferred file, which the IP module matches by calculating the CRC using the built-in STM32 CRC unit. Besides that and the firmware image obfuscation there are no security features such as file signatures that would prevent anyone from pushing a modified firmware file.

Firmware files of Paradox products come in the PUF file format, which is a container that has some information about the firmware file and an obfuscated firmware image. Obfuscated firmware images can be extracted from the PUF container using the open source tool pufparse.

The obfuscation algorithm can be found by reverse engineering the HexToPuf.exe binary from the BabyWare software package. The algorithm itself is trivial to reverse, it uses only two bytes as an “encryption” key, these bytes are just static product and family IDs of a specific IP module version. We wrote a tool to decrypt and encrypt firmware images, you can find it here.

The following video shows a proof-of-concept where we upload a modified firmware to an IP module. The firmware was modified in a rudimentary way, by just changing an HTML file, in a real world attack a proper backdoor would be created that would give persistent access to the internal network the IP module is connected to.

As the video shows we have created an upgrade server emulator, which is started on a specified port, in this case 11011. We then use our paradox protocol tool to send a cmdBootLoader IP command with the IP address of the host where the listener is running. The IP module connects to the upgrade server immediately and the server starts the transfer. When the transfer is finished the module reboots and in a couple of seconds loads the modified firmware.

Fuzzing the protocol

All of the previously described vulnerabilities do not require breaking the parser of the protocol. To see how robust the protocol parsing is, and if we can cause any memory corruptions, we implemented a simple fuzzer for IP messages. A single IP module was fuzzed with a single network thread. Running this fuzzer for 24 hours has resulted in the following:

- 57 pre-auth packets that probably cause a memory corruption and results in a crash/reboot of the device.

- 3 pre-auth packets that cause a denial-of-service until the device is reset by power cycling. We did not investigate these crashes in depth, as you can already just use existing protocol features to do anything you want. The number of crashes we logged though, does suggest that the protocol parser is as broken as the protocol itself.

Defense recommendations

If you have one of these devices on your network, ensure that it is behind a firewall and only a whitelist of IPs can connect to it. Ideally such a device should be put inside an isolated network.

Final thoughts

Considering the small amount of time we spent to find these critical risk issues it is highly likely that more of them exist. Further research could be done on other IP and Serial message commands, as we did not investigate them all. The SWAN protocol also seems like an interesting, semi recent addition to their legacy codebase, potentially ripe for misuse. As we could not inform Paradox about these vulnerabilities, due do them ignoring our contact attempts, we will not be releasing the exploit code now.

Disclosure timeline:

- 2021-03-10 – Contacting Paradox support at support@paradox.com about security vulnerabilities. Automatic ticket created.

- 2021-03-11 – Ticket closed, no response from Paradox.

- 2021-05-03 – Contacting Paradox support at support@paradox.com about security vulnerabilities. Automatic ticket created.

- 2021-05-04 – Ticket closed, no response from Paradox.

- 2021-05-11 – Article released.

About Us

Critical Security was established in 2007 by a group of cyber security enthusiasts. Since its establishment, the company has been providing high-quality security assessments and penetration tests to various organizations, helping them identify and mitigate potential security threats.